- Home

- Sasha Stephenson

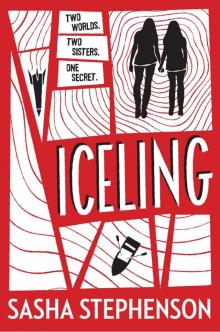

Iceling

Iceling Read online

An Imprint of Penguin Random House

Penguin.com

Copyright © 2016 Penguin Random House LLC

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Ebook ISBN: 9780698153080

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Acknowledgments

ONE

SO, HERE WE are, Dave and I. The two of us, alone in my room, with no adult supervision, ostensibly engaged in homework. My sister, Callie, is downstairs watching a thing on the Internet about carnivorous plants. Or at least that’s what she was doing the last time I checked, about forty-five minutes ago, which is usually how long I tend to go without checking in on her.

The thing about Dave is that he’s tall, like, six two, and he’s got these real broad shoulders, and he’s always wearing these baseball hats but only for teams that don’t exist anymore. He’s better than me at social studies, and I’m better than him at reading, writing, and most of the sciences. We actually do do homework together sometimes, but that’s not what we’re doing right now.

“Did you hear that?” Dave says, pulling away from me for a moment. And I do hear it: Downstairs there is a crashing and gnashing, a weeping and moaning.

Oh no, I think, and I run downstairs.

On the floor I find Callie, her eyes wide open, her legs curled up into herself while her arms flail around, as if she’s trying to dig her way through the air. For a second all I can do is stand there, looking at her on the ground, making sounds. Like what, I can’t even try to say.

Dave’s been around Callie plenty of times, but he’s never seen her like this before. I don’t think I’ve ever even seen her like this before. Callie gets these fits sometimes, and I’m usually pretty good at calming her down, but this one is a bit scarier than what I’m used to. And I think I need to get Dave out of here and help my sister.

“Dave, I’m really sorry, but I have to take Callie to the hospital and—”

But before I can finish, Dave is picking Callie up off the floor. He’s telling me to get my keys, and I do, and then I’m grabbing our coats and closing the door and clicking the dead bolt to lock it. I head out to the driveway and see that Dave’s already got Callie in the backseat, strapped in and everything. And then there’s Dave in his car, backing out of the driveway to clear the way for me, and then he parks by the curb and sits there waiting to watch us go off, and he looks at me, and I know it’ll be okay.

Well, “okay” isn’t the word. But I know that Callie’s big fit and my leaving Dave so abruptly isn’t what’s going to hurt whatever it is we have together. I smile at that, and then I don’t, because I don’t really know what this is with me and him—I don’t really know what I want it to be. But, as I’m sure you can imagine, I have bigger things to worry about right now, like my sister, Callie, and her weirdly giant fit.

Weird for Callie, that is. Lots of people these days have fits, sudden loss or acquisition of new language, mild levitations. Last month 60 Minutes ran a piece on a group of children in India who went to bed knowing only their native language and woke up speaking fluent French. When I was little I knew some kids who claimed they could move things with their minds, but I never saw any of them pull off that comic book trick with my own eyes, so the jury’s out on them. But the other stuff is real, and this is just how things are around here on earth these days. You read an article about a mother lifting a car to save her baby, and there are way more explanations than just “adrenaline rush sparked by maternal instincts.”

Callie’s pale green eyes lock with mine. She’s looking at me like she wants to say she’s sorry about all this. And also that this hurts and she doesn’t understand it either. She’s looking at me like “Yes, we both hate this,” and I want to tell her, “I know, I love you, it’s okay.” And I do, I say it out loud, and then I tap out the words with my eyes just for her. I turn my head from the road for a moment and blow her a kiss. I think she tries to too, but she can’t make her mouth work right right now, so instead she just keeps looking at me with those sorry eyes.

You’d think after sixteen years of Callie not talking, I’d be used to it by now. You’d think after sixteen years of having a sister who can’t speak, or read, or even understand any language at all, nights like these wouldn’t bother me much. That the way Callie is wouldn’t keep surprising me day after day.

Dad says Callie is “non-lingual.” Me, I’m not so certain. I keep trying different languages and cadences with her to see if anything clicks. It never does. We have this thing between us that Mom calls language, but it isn’t that. It isn’t a language. It’s more that we have this way of reading each other. Of being very specific with our eyes and our faces, our postures, our vibes. We have these signals, almost, or at least I think we do.

But if Callie can talk to anyone, it’s plants. Not that plants are people. I know plants aren’t people. But she’s always been good with them, ever since she was small. She seems so calm and just generally at home around them, with her hands in the dirt, her eyes shut—not tightly, but just softly closed. As if when she’s with them, they help her remember some other home. Which is weird, considering she was born in the Arctic.

Or at least the Arctic is where Dad and his research crew found her, along with a hundred or so other infants, in a ship, all alone. Not a parent or any other human in sight, just a hundred or so babies all alone in the Arctic. I shiver, and it’s not just from the thought of the cold.

I look at Callie in the rearview. Her eyes are still sorry, but her face is going toward the window, and for a second I think she’s watching the lights of the highway count us down to the hospital. But then I realize she’s looking at herself and her sad and sorry eyes.

“Hey, kid sister,” I say. “Callie?” I say. She almost turns around.

The fits have been getting worse. Mom calls them “conniptions,” but there’s no way I’ll ever say that word out loud where anyone could hear it. Whatever they are, they�

��re getting worse, and they’re happening to my sister, who can’t ever tell me what it’s like to be her. Whenever I look into her eyes I feel like I can almost see it, except I know that’s just me wishing I could tell a story about a time and place where everyone can be understood, where we are all able to really get to know another person and hold them close and find real comfort in that, and then we all have a pizza party and build a tent in the living room and make a scale model of the solar system and hang it from the ceiling and then go to college and then get good jobs, and the economy is stable, and the government is just, and the story only ends when nobody is scared of being alive anymore.

Stories are pretty great if you don’t mind crying sometimes.

Callie’s eyes are full of something I don’t have the words for, and the lights of the hospital are just ahead.

TWO

IN THE HOSPITAL, everything is fine.

Callie looks at the lights and the door, and after we find a parking spot close to the entrance she seems to pull it together enough to help me help her up and out of the backseat and into the lobby. I open the door for Callie, because the child locks have been on for the past few weeks, and if you were to ask me why, then I’d tell you a story about coming home one day and finding Callie sitting in the backseat of my car. Or another story that’s different but the same, about coming home and finding Callie furiously packing and unpacking suitcases. And anyway, the child locks have been on for the past few weeks.

Callie grows calmer with each step we take toward the automatic doors, and I can’t help thinking that it might not be fair for me to assume that she’s actually pulled herself together. I can’t tell if this is a situation she even has the ability to pull together, whether or not her growing calm after the worst of these fits is her attempt to control something uncontrollable, something big and terrifying that grips her in a scary part of her brain she can’t ever do a thing about. I want to ask someone about this, but I don’t really know who or how to ask in such a way that won’t make them look at me weird, or even worse, look at Callie weird, the way they’d look at someone who they think should be taken away to be observed in an environment away from “outside factors.” Because I’m pretty sure I fall under the category “outside factors.”

“Outside factors, kid sister,” I say to Callie, and she smiles a bit but doesn’t look at me. I should talk to her more, I think. “I should talk to you more, huh?” I say, and she smiles a bit more, and I smile back. Finally she looks at me and then again over to the hospital, but her smile’s gone now. Her mouth took it back and instead gave her an expression I don’t know how to read.

“Sometimes,” I tell her, “I think we’re like different editions of the same book.”

I know that this doesn’t make any sense, but it maybe sounds nice.

AND SO HERE we are, in the hospital.

As a government-mandated condition of caring for an Arctic Recovery Orphan (which is the official term for Callie and the others found in the Arctic when they were infants), there are regularly scheduled check-ins with what my parents call a “caseworker.” What Callie’s particular “case” is is something I couldn’t tell you if I wanted to. I would, though. Want to. But nobody asked me. Or told me. Nobody tells me much of any use, at any rate.

Anyway, here we are in the lobby, and Jane, Callie’s caseworker, is walking toward us in a professional hurry, walking quickly yet in such a way that it’s clear she doesn’t want anyone to think she’s walk ing toward anything urgent, which only makes everything look even more urgent, and nobody is comfortable about any of this.

“Hi, Lorna,” Jane says. She’s coming out to greet us now, walking down a hallway I’ve never been allowed to enter. She’s wearing a white lab coat, but otherwise she’s dressed like a vaguely stylish but relatively severe woman who is somewhere between older-than-college and probably-younger-than-my-parents. “I have to say,” she goes on, “it’s a bit surprising to see you so soon after Callie’s last check-in.” She puts her hand on my shoulder a beat or two after she finishes her sentence, as if she had to think of the gesture before making it. Either that or I just don’t like her and find everything she does slightly annoying. “I have to ask: Is everything okay?”

“Oh, sure. I drove here at eleven o’clock on a school night because things are just swell” is what I don’t say. I stare at her for a minute, then I tell her, “Callie had a fit, and it was not the smallest?” Jane nods and looks from me to Callie. “She was watching this carnivorous plant doc on YouTube,” I continue. “And then all of a sudden I heard her, having the fit, from upstairs with my door closed. When I went down and found her, I got worried enough to get her in the car and come down here.” And I stop there, because that is roughly as honest as I am willing to be with Jane.

I know that with doctors you’re only hurting yourself if you don’t tell them how bad you’re really feeling on a pain scale of one to ten—if they don’t know how bad you’re hurting, then they don’t know how to treat you. But the thing about doctors is that after you tell them your symptoms, they tell you what’s going on and what they need to do to fix it. And that’s not something I feel like I get with Jane.

“Oh dear,” says Jane. “Well, let’s take her back and see if we can’t figure out what the trouble is. Poor Callie, we love her so. She’s just one of the sweetest girls I’ve ever been able to work with.”

“Great,” I say, then catch myself. “I mean, I like her too,” I say. “I’ll need her back, though. I’ve kind of gotten used to having her around the house.”

Jane just looks at me, and I look right back. She smiles, then takes Callie by the hand and goes through the doors and down that hall, and once again I’m not allowed to follow.

I go back to the lobby and sit down in a waiting room chair. I text Dave, Dad, and Mom, in that order. Dad gets confused by group texts, which I learned in a pretty awkward way that I’d rather not go into, so Mom and I agreed that we would not do group texts, for the sake of all of us.

Everyone has something to say in response, but mostly I don’t care. Right now, all I care about is Callie and about getting home and going to bed. I tell my parents I can handle it, and Dad responds with nothing but confidence, and Mom responds with a hesitant OK, but call us if u need us and we’ll be right there!!!! I text Dave a whole bunch of kiss emojis and tell him again how I’m sorry, and he tells me not to even think about it, there’s nothing to even be sorry about, and I almost believe him.

The main question people have for us is how Callie, non-lingual and subject to fits, spends her days. Well, one of the perks of my mom’s position as a tenured college professor is that she usually ends up teaching, like, two classes a semester. There are office hours, but she shares a lab with Dad in our house, which means there’s pretty much always someone at home with Callie. And when there’s a blue moon and all of us have obligations outside the house at the same time, there’s a never-ending supply of grad students looking to get on my parents’ good sides.

I scan the hospital waiting room. There are a couple of coughing children sitting near me, along with a whole handful of parents whose expressions range from worried to bored. Suddenly, two more teens on the other side of the room start having mild seizures, and I’d say they were Arctic Orphans too, except they look like they’re too old. One of the parents seems to think everything’s totally fine, nothing to worry about here, and the other kid’s parent is totally freaking out. But from the way she’s freaking out, I can’t tell if it’s more that she’s embarrassed, as if she’s hoping nobody else sees this, or that somebody will come to help very, very soon. Then I start thinking that maybe it’s both of these things. That she’s hoping somebody’s going to come and say to her child, “I know this is scary and hard, but it’s okay, and it’ll be okay.” Wouldn’t it be nice if there were someone who could just come up to you and say that, and you would believe them, and it would be t

rue?

The freaked-out woman is starting to put me on edge, so I look away and see, sitting across from me, Stan.

Stan is like me in that he has a brother who is also an Arctic Recovery Orphan, whose name is Ted, I think, but I’m not 100 percent sure. Ned? Anyway, I can’t remember the last time I saw Stan, but here he is now, in gym shorts and new but dirtied Nikes and a hoodie. We’ve been together in this waiting room enough times that I smile and wave at him now. But we’ve never really talked before, and never outside the hospital. For some reason there isn’t, like, I don’t know, a listserv or a message board for people like us. It’s not as if the government or whoever makes up the rules for our sisters and brothers has actively tried to make sure that none of us ever meet, but it’s also not as if anyone’s ever encouraged it.

I’ve seen Stan, like, three times, and I’ve never seen his brother before. Once, once, maybe three years ago, I remember he and I were sitting with our parents in this very same room, waiting for Callie. Jane, her caseworker, came out alone, and Stan and I both stood up to greet her, and his eyes fell a bit when she came over to us instead of him. That’s how I figured out who Stan was and why he was there. Later I saw Jane talking to him, and I heard her say “conniption,” and it is not like everyone just goes around saying “conniption” like it’s a fashionable new turn of phrase. So it’s always a bit weird to see him here, I guess. Seeing Stan could mean that his brother and my sister are having seizures at the same time.

I want to ask Stan if his brother’s getting weirder too. And also about Jane and what he thinks of her.

See, Jane always talks to me in this sweet, concerned, authority-figure voice. But her eyes are cold. She’ll be smiling at me and calling me “dear,” but she’ll look at me with these eyes that let me know that my life or death would mean nothing to her. Maybe I’m just being melodramatic or projecting because here she is, this stranger who is in total control of Callie and what happens to her during check-ins and after she has fits. And because I know all about what’s involved in caring for and about Callie, knowing that is a little terrifying to me. And I’ve seen how her posture changes as soon as she walks away from me, like she only cares about making me see her as kind and nurturing for as long as I’m in her line of sight. Anyway, suffice it to say, I’m not her biggest fan.

Iceling

Iceling