- Home

- Sasha Stephenson

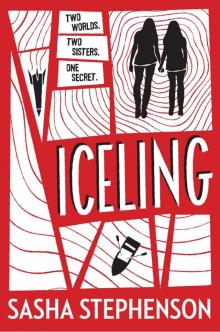

Iceling Page 24

Iceling Read online

Page 24

“And also to tell you,” he interrupts, “I heard from Mom that you guys had a party after we left, which I can’t say I’m surprised by, and in fact I have to say I’m a little proud.” And then I hear a door closing on his end.

“Listen, Lorna,” he says in a hushed voice just above a whisper, “very, very carefully. As far as I know, Bobby and I are the only ones who know about this phone. I don’t know how much time I have, so just listen. Don’t talk.”

And, as much as I want to talk, as much as I want to demand answers to questions worth asking, I hear the tone in his voice, and I bite my tongue. I take a deep breath and give the thumbs-up to Emily and Stan, who are watching me with terrified eyes.

“I know you talked to Mom before they started herding everyone north. Reports about what ultimately happened have been scarce, so I’m guessing whatever it was, it wasn’t good. The last broadcast we heard said that one of the AROs tossed a pod at a drone, and then some kid soldier fired off a rocket without orders. I swear to God, I thought you were dead. Your mother worries you might be. Me, though, I didn’t see the champion of my heart getting blown up in a governmental cluster, no matter what sort of payloads were involved.” He pauses now, and I almost venture to say something, but then I miss my chance. “I just want to tell you,” he says, “everything. About that day, about Callie. We were up there to check on those anomalies,” he says, “which you already knew. And I’m sure you noticed those same anomalies for yourself when you were up there. We were there on a grant, a government grant, which is also probably no big surprise to you now.

“There weren’t any docks there back then. We had to beach the boat, and I made two interns stay with it, planting themselves in the frozen sand, clinging to ropes, with nothing but the vague hope of getting course credit tethering them there. We landed where the new docks are now, which is why the new docks are there now. There was this hole in the ground, and we heard some sounds coming up out of it. Did you see the shed? They built a shed over it. Not even I know what the hell they found in there or what they were looking for. But we made our way there, among those goddamn trees, covered in snow and ice. And we stayed for a while, taking photos. We made it past the hills. The hills sing. I don’t know if you heard them. They sing. Not like a song. They resonate around the trembling expanse.

“And the ice field is trembling, viciously. I go out, and I test it. Because the readings don’t make any sense, and the sky doesn’t make any sense. It’s purple and yellow, but only over the field. We can see the sky going gray all around this, just normal and flat and endless like the sky gets out there. And the air smells like lightning. Which I told you I hoped you would never get to smell. There’s always a change with lightning around. It’s this sort of math you can’t predict. And it always, always alters something. Irretrievably. And then this guy . . . this guy just pops up out of the ground. He stares at us. All he does is stare. And the ice is breaking apart, and I’m standing on it, because the readings don’t make any sense here, because even though it’s quaking, it’s more than stable enough to stand on.

“The guy stands there and stares on and on, and then the pods come up. All at once, they poke out through the ice. It was like watching one of those time-lapse films of plants pushing their way up out the soil. Except the soil is a field of solid ice staying solid above a core that’s just barely not magma. Just barely. They look like flowers. Like flowers wrapping a gift. And then they unwrap. They open. One pod at a time. And the sound of thunder is everywhere. And I see, at my feet, a baby. And my own baby girl, she’s back home, safe in southeastern Pennsylvania, on Carpenter Street. I pick up the baby girl in front of me, and I look in her eyes, and I have no idea what I’m seeing, but I can’t look away from her. And I can’t leave her there. If I am to believe the readings, then I should believe that the island is falling apart, but when I look around and feel myself standing there on that troubled earth, that’s not what I believe will happen at all. That guy is still there, staring at us. He looks like he’s about thirty years old, give or take a couple of years. And like he doesn’t know a thing about babies. And I just go. I run from pod to pod, my students hustling along beside me, helping me grab these babies. Some of them, Lorna . . . Have you ever seen premature babies? How small they are? Some of these kids just . . . they were like dust. Their skin looked like it was built to never see the sun. They were so pale it was like I could see through them, see their little hearts not beat but just give out. Just give out right in front of me, Lorna.

“We kept running, and we grabbed as many as we could, tucked them in our jackets. I had maybe six in there, holding them close, trying so hard not to crush them, to just keep them warm and alive.

“We saved them, we thought. That’s what we thought we were doing. And Callie. I couldn’t leave her there. I couldn’t. Maybe that’s selfish as hell. I think it is now.

“Nobody else knows this. My assistants, my students, I don’t know what happened to them. I can’t. I don’t think about it—that’s how I live with it. Your mom knows. Now you. Jane doesn’t know. The main way I know your mom still loves me is that Jane still doesn’t know. She loves me enough not to go to her. Lorna, I love you, and I’m sorry.” His voice quivers a bit, and I find I don’t even want to say anything to him. I just want to get off the phone.

“After that, Lorna,” he goes on. “After the plants came up, those perfect little infants nestled in the mouths of those pods . . . the things we saw were just—”

And the phone call ends.

I don’t know how or why it was allowed to last that long.

I know my dad. I know he thought he was being a good person. I know he thought he was doing the right thing. And I don’t know what happened after that. I don’t know what happened to my dad. I don’t know if the dad I know is just his story of who he thought he was going to be before that day.

His voice was so strange on the phone. My mouth is moving and moving, trying to tell Stan and Emily what happened, and I can’t make a sound. I can’t. I can hardly breathe, and there is this weight, like my heart is a rock that just dropped into my stomach, and I just want to throw it up, to just get it out of me and breathe, and I can’t. I can’t. I don’t know how right now.

I run up above the deck, and I fling the phone into the sea. I want so badly to hear Dad’s voice again, to have him tell me that everything is okay. But I don’t know who else was listening. As much as Dad may believe that he and Bobby are the only ones who know about the phone, there’s no way to prove it. Someone could have been tracking it—and us. I throw my regular phone overboard too, because it might still be pinging out a signal. Then I put my face in my hands. I put my face in my hands, and I stay like that for a while, not wanting to see or hear anything else.

I hear a sound like a whisper, near my ear. Callie’s holding me. I know it’s Callie because she smells like Callie, because I have smelled Callie every day for almost every day of her life. She peels my hands from my face slowly, like she’s unwrapping a present. She wipes my tears away, and I just make new ones. She looks at me. She makes her face look like mine. She sits there with me and makes her face look like mine, and I have my first funny thought in a while, which is: If that’s what I look like, I should stop that. So I try to. And she smiles at me.

We sit there like that all night, watching the sea. Dolphins do this thing where they have to breathe, but they also have to sleep, so they sort of float there like logs, turning and breathing and turning and breathing. The water’s mostly calm. The wind has been getting warmer over the past several days. The air smells like it always smells: wet, and salty, and like fish living and dying and breeding all around us.

THE SUN’S COMING up. It’s dawn, and the sky is anything but clear, and a fog is rising and settling all around us. I’m wracked and ragged from last night, from this whole life, which is, I am now realizing, mine. So here I am. On the deck of this boat, a

nd my sister is here, holding my hand and watching the sea with me. Our feet are dangling over the edge, getting damp in the foggy mist. Callie reaches into her pocket and pulls out two crackers. She puts one in her mouth, and she puts the other in mine.

I don’t know what comes next, and I couldn’t even begin to imagine it without screwing it up, but whatever it is, it’s my sister and me. Here. Now. And with this—with this—I say, Fine. I can take it. I dare you.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Liz Tingue, without whom this book wouldn't be here, and to Rebecca Novack for the notes and attention. Thanks to Nalini Edwin, Sarah Hallacher, Andrea McGinty, and Lauren Wilkinson for their friendship and eyes along the way. Thanks to Maggie Logan for being the best, and to my parents and brother for their endless love and support.

What’s next on

your reading list?

Discover your next

great read!

* * *

Get personalized book picks and up-to-date news about this author.

Sign up now.

Iceling

Iceling